TODO

- Add about readline vs libedit vs editline

REFERENCES:

BSD licenced readline alternative

https://forums.freebsd.org/threads/bsd-licenced-readline-alternative.68310/The secret weapon of Bash power users (opensource.net)

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=39799767The secret weapon of Bash power users - OpenSource.net

https://opensource.net/the-secret-weapon-of-bash-power-users/

Escape sequence - Terminal and Printers Handbook Glossary:

Escape sequence

A special sequence of ASCII characters beginning with the escape character (ESC) used to send special text-formatting or editing commands to terminals. See also: [ASCII](https://vt100.net/docs/tp83/glossary.html#a09)

Line discipline (LDISC) aka Terminal I/O:

A line discipline (LDISC) is a layer in the terminal subsystem in some Unix-like systems.

The terminal subsystem consists of three layers:

* the upper layer to provide the character device interface,

* the lower hardware driver to communicate with the hardware or pseudo terminal,

* the middle line discipline to implement behavior common to terminal devices.

Some Unix-like systems use STREAMS to implement line disciplines:

XTerm Control Sequences - aka ctlseqs - XTerm by Thomas Dickey (invisible-island.net):

Definitions

-----------

Many controls use parameters, shown in italics. If a control uses a

single parameter, only one parameter name is listed. Some parameters

(along with separating ; characters) may be optional. Other characters

in the control are required.

C A single (required) character.

Ps A single (usually optional) numeric parameter, composed of one or

more digits.

Pm Any number of single numeric parameters, separated by ; charac-

ter(s). Individual values for the parameters are listed with Ps .

Pt A text parameter composed of printable characters.

Control Bytes, Characters, and Sequences

----------------------------------------

ECMA-48 (aka "ISO 6429") documents C1 (8-bit) and C0 (7-bit) codes.

Those are respectively codes 128 to 159 and 0 to 31. ECMA-48 avoids

referring to these codes as characters, because that term is associated

with graphic characters. Instead, it uses "bytes" and "codes", with

occasional lapses to "characters" where the meaning cannot be mistaken.

Controls (including the **escape code 27**) are processed once:

---- snip ----

C1 (8-Bit) Control Characters

-----------------------------

The xterm program recognizes both 8-bit and 7-bit control characters.

It generates 7-bit controls (by default) or 8-bit if S8C1T is enabled.

The following pairs of 7-bit and 8-bit control characters are equiva-

lent:

---- snip ----

ESC [

Control Sequence Introducer (CSI is 0x9b).

---- snip ----

ESC ]

Operating System Command (OSC is 0x9d).

---- snip ----

Non-VT100 Modes

---------------

Tektronix 4014 Mode

-------------------

Most of these sequences are standard Tektronix 4014 control sequences.

Graph mode supports the 12-bit addressing of the Tektronix 4014. The

major features missing are the write-through and defocused modes. This

document does not describe the commands used in the various Tektronix

plotting modes but does describe the commands to switch modes.

Some of the sequences are specific to xterm. The Tektronix emulation

was added in X10R4 (1986). The VT240, introduced two years earlier,

also supported Tektronix 4010/4014. Unlike xterm, the VT240 documenta-

tion implies (there is an obvious error in section 6.9 "Entering and

Exiting 4010/4014 Mode") that exiting back to ANSI mode is done by

resetting private mode 3 8 (DECTEK) rather than ESC ETX . A real Tek-

tronix 4014 would not respond to either.

BEL Bell (Ctrl-G).

BS Backspace (Ctrl-H).

TAB Horizontal Tab (Ctrl-I).

LF Line Feed or New Line (Ctrl-J).

VT Cursor up (Ctrl-K).

FF Form Feed or New Page (Ctrl-L).

CR Carriage Return (Ctrl-M).

ESC ETX Switch to VT100 Mode (ESC Ctrl-C).

ESC ENQ Return Terminal Status (ESC Ctrl-E).

ESC FF PAGE (Clear Screen) (ESC Ctrl-L).

ESC SO Begin 4015 APL mode (ESC Ctrl-N). This is ignored by xterm.

ESC SI End 4015 APL mode (ESC Ctrl-O). This is ignored by xterm.

ESC ETB COPY (Save Tektronix Codes to file COPYyyyy-mm-dd.hh:mm:ss).

ETB (end transmission block) is the same as Ctrl-W.

ESC CAN Bypass Condition (ESC Ctrl-X).

ESC SUB GIN mode (ESC Ctrl-Z).

ESC FS Special Point Plot Mode (ESC Ctrl-\).

ESC 8 Select Large Character Set.

ESC 9 Select #2 Character Set.

ESC : Select #3 Character Set.

ESC ; Select Small Character Set.

OSC Ps ; Pt BEL

Set Text Parameters of VT window.

Ps = 0 ⇒ Change Icon Name and Window Title to Pt.

Ps = 1 ⇒ Change Icon Name to Pt.

Ps = 2 ⇒ Change Window Title to Pt.

Ps = 4 6 ⇒ Change Log File to Pt. This is normally

disabled by a compile-time option.

Example: Change XTerm Window Title

Sequence is: OSC Ps ; Pt BEL

This works in FreeBSD 12

(Shell: tcsh; TERM: xterm-new; TERMCAP set?: Yes; Window Manager: Fvwm)

NOTE:

From the man page for xterm(1):

Window and Icon Titles

Some scripts use echo with options -e and -n to tell the shell to

interpret the string “\e” as the escape character and to suppress a

trailing newline on output. Those are not portable, nor recommended.

Instead, use printf (POSIX).

For example, to set the window title to “Hello world!”, you could use

one of these commands in a script:

printf '\033]2;Hello world!\033\\'

printf '\033]2;Hello world!\007'

printf '\033]2;%s\033\\' "Hello world!"

printf '\033]2;%s\007' "Hello world!"

The printf command interprets the octal value “\033” for escape, and

(since it was not given in the format) omits a trailing newline from

the output.

Some programs (such as screen(1)) set both window- and icon-titles at

the same time, using a slightly different control sequence:

printf '\033]0;Hello world!\033\\'

printf '\033]0;Hello world!\007'

printf '\033]0;%s\033\\' "Hello world!"

printf '\033]0;%s\007' "Hello world!"

The difference is the parameter “0” in each command. Most window

managers will honor either window title or icon title. Some will make

a distinction and allow you to set just the icon title. You can tell

xterm to ask for this with a different parameter in the control

sequence:

printf '\033]1;Hello world!\033\\'

printf '\033]1;Hello world!\007'

printf '\033]1;%s\033\\' "Hello world!"

printf '\033]1;%s\007' "Hello world!"

- OSC (Operating System Command (OSC is 0x9d) is:

ESC ]

To be used by printf(1), OSC is:

\033]

NOTE:

ESC = 033 in ASCII (in octal - because printf(1) requires it in octal)

NOTE:

printf(1) uses a backslash (\) for octal number representation.

- Ps (control for chaning change the window title) is:

2

- After OSC and Ps controls, the next parameter is the separating semicolon character:

;

- Pt (a text parameter composed of printable characters) is:

My Window Title

- BEL is:

\007

NOTE:

BEL = 007 in ASCII (in octal - because printf(1) requires it in octal)

NOTE:

printf(1) uses a backslash (\) for octal number representation.

$ printf '\033]2;My Window Title\007'

“Although using vt escape sequences (as above) is easy and supported by most if not all commonly-used unix terminal emulators, die-hards will insist that you learn to use the tput(1) command:”

printf "Here is a %sbold red%s word\n" "$(tput bold)""$(tput setf 4)" "$(tput sgr0)"

“IMHO, figuring out the magic tput symbols (see man 5 terminfo on a debian/ubuntu system) is not as easy as looking up the xterm control sequences (google the last three words), but YMMV”.

In my tests, it partially worked in a bhyve VM running Debian GNU/Linux 11 (bullseye) in bash shell: it displayed ‘bold’ in bold but not ‘red’ in red colour.

The following works in FreeBSD 12 (Shell: tcsh; TERM: xterm-new; TERMCAP set?: Yes; Window Manager: Fvwm):

- With

boldfor the capability name (capname - the short name used in the text of the terminal capability database):tput bold,tput AF,tput me:

$ printf "Here is a \033[0;1mbold %sred %sword \n" `tput bold` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Here is a bold red word

Without zero in the escape sequence ([;1m instead of [0;1m):

$ printf "Here is a \033[;1mbold %sred %sword \n" `tput bold` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Here is a bold red word

With %s format character for string format in printf(1) utility (%s\033[0;1m instead of \033[0;1m):

$ printf "Here is a %s\033[0;1mbold %sred %sword\n" `tput bold` `tput me` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Here is a bold red word

- With

mdfor the capability name (TCap code) in the text of the terminal capability database:

$ printf "Here is %sa %s\033[0;1mbold %sred %sword\n" `tput md ` `tput me` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Without zero in the escape sequence ([;1m instead of [0;1m):

% printf "Here is %sa %s\033[;1mbold %sred %sword\n" `tput md ` `tput me` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Here is a bold red word

Without %s format character for string format in printf(1) utility (Here is a instead of Here is %sa):

$ printf "Here is a %s\033[;1mbold %sred %sword\n" `tput md ` `tput AF 1` `tput me`

Here is a bold red word

NOTE:

tput AF 0: black, tput AF 1: red, tput AF 2: bright green, tput AF 3: yellow, tput AF 4: blue, tput AF 5: magenta, tput AF 6: cyan, tput AF 7: white

From the man page for terminfo(5) terminal capability database on FreeBSD 12:

---- snip ----

Predefined Capabilities

The following is a complete table of the capabilities included in a

terminfo description block and available to terminfo-using code.

In each line of the table,

The variable is the name by which the programmer (at the terminfo

level) accesses the capability.

The capname is the short name used in the text of the database, and is

used by a person updating the database. Whenever possible, capnames

are chosen to be the same as or similar to the ANSI X3.64-1979 standard

(now superseded by ECMA-48, which uses identical or very similar

names). Semantics are also intended to match those of the

specification.

The termcap code is the old termcap capability name (some capabilities

are new, and have names which termcap did not originate).

Capability names have no hard length limit, but an informal limit of 5

characters has been adopted to keep them short and to allow the tabs in

the source file Caps to line up nicely.

---- snip ----

These are the string capabilities:

Variable Cap- TCap Description

String name Code

---- snip ----

set_a_foreground setaf AF Set foreground

color to #1, using

ANSI escape

---- snip ----

exit_attribute_mode sgr0 me turn off all

attributes

---- snip ----

Most color terminals are either “Tektronix-like” or “HP-like”:

* Tektronix-like terminals have a predefined set of N colors (where N

is usually 8), and can set character-cell foreground and background

characters independently, mixing them into N * N color-pairs.

* On HP-like terminals, the user must set each color pair up

separately (foreground and background are not independently

settable). Up to M color-pairs may be set up from 2*M different

colors. ANSI-compatible terminals are Tektronix-like.

Some basic color capabilities are independent of the color method. The

numeric capabilities colors and pairs specify the maximum numbers of

colors and color-pairs that can be displayed simultaneously. The op

(original pair) string resets foreground and background colors to their

default values for the terminal. The oc string resets all colors or

color-pairs to their default values for the terminal. Some terminals

(including many PC terminal emulators) erase screen areas with the

current background color rather than the power-up default background;

these should have the boolean capability bce.

While the curses library works with color pairs (reflecting the

inability of some devices to set foreground and background colors

independently), there are separate capabilities for setting these

features:

* To change the current foreground or background color on a

Tektronix-type terminal, use setaf (set ANSI foreground) and setab

(set ANSI background) or setf (set foreground) and setb (set

background). These take one parameter, the color number.

The SVr4 documentation describes only setaf/setab; the XPG4 draft

says that "If the terminal supports ANSI escape sequences to set

background and foreground, they should be coded as setaf and setab,

respectively.

* If the terminal supports other escape sequences to set background

and foreground, they should be coded as setf and setb,

respectively. The vidputs and the refresh(3X) functions use the

setaf and setab capabilities if they are defined.

The setaf/setab and setf/setb capabilities take a single numeric

argument each. Argument values 0-7 of setaf/setab are portably defined

as follows (the middle column is the symbolic #define available in the

header for the curses or ncurses libraries). The terminal hardware is

free to map these as it likes, but the RGB values indicate normal

locations in color space.

Color #define Value RGB

black COLOR_BLACK 0 0, 0, 0

red COLOR_RED 1 max,0,0

green COLOR_GREEN 2 0,max,0

yellow COLOR_YELLOW 3 max,max,0

blue COLOR_BLUE 4 0,0,max

magenta COLOR_MAGENTA 5 max,0,max

cyan COLOR_CYAN 6 0,max,max

white COLOR_WHITE 7 max,max,max

---- snip ----

Highlighting, Underlining, and Visible Bells

If your terminal has one or more kinds of display attributes, these can

be represented in a number of different ways. You should choose one

display form as standout mode, representing a good, high contrast,

easy-on-the-eyes, format for highlighting error messages and other

attention getters. (If you have a choice, reverse video plus half-

bright is good, or reverse video alone.) The sequences to enter and

exit standout mode are given as smso and rmso, respectively. If the

code to change into or out of standout mode leaves one or even two

blank spaces on the screen, as the TVI 912 and Teleray 1061 do, then

xmc should be given to tell how many spaces are left.

Codes to begin underlining and end underlining can be given as smul and

rmul respectively. If the terminal has a code to underline the current

character and move the cursor one space to the right, such as the

Microterm Mime, this can be given as uc.

Other capabilities to enter various highlighting modes include blink

(blinking) bold (bold or extra bright) dim (dim or half-bright) invis

(blanking or invisible text) prot (protected) rev (reverse video) sgr0

(turn off all attribute modes) smacs (enter alternate character set

mode) and rmacs (exit alternate character set mode). Turning on any of

these modes singly may or may not turn off other modes.

If there is a sequence to set arbitrary combinations of modes, this

should be given as sgr (set attributes), taking 9 parameters. Each

parameter is either 0 or nonzero, as the corresponding attribute is on

or off. The 9 parameters are, in order: standout, underline, reverse,

blink, dim, bold, blank, protect, alternate character set. Not all

modes need be supported by sgr, only those for which corresponding

separate attribute commands exist.

For example, the DEC vt220 supports most of the modes:

tparm parameter attribute escape sequence

none none \E[0m

p1 standout \E[0;1;7m

p2 underline \E[0;4m

p3 reverse \E[0;7m

p4 blink \E[0;5m

p5 dim not available

p6 bold \E[0;1m

p7 invis \E[0;8m

p8 protect not used

p9 altcharset ^O (off) ^N (on)

We begin each escape sequence by turning off any existing modes, since

there is no quick way to determine whether they are active. Standout

is set up to be the combination of reverse and bold. The vt220

terminal has a protect mode, though it is not commonly used in sgr

because it protects characters on the screen from the host's erasures.

The altcharset mode also is different in that it is either ^O or ^N,

depending on whether it is off or on. If all modes are turned on, the

resulting sequence is \E[0;1;4;5;7;8m^N.

---- snip ----

On this system, FreeBSD 12 (Shell: tcsh; TERM: xterm-new; TERMCAP set?: Yes; Window Manager: Fvwm), changing foreground colour works with setaf, that is AF, so the xterm on this system is a Tektronix-type terminal (see above excerpt from the man page for terminfo(5)).

From Perl Programmers Reference Guide:

$ man Term::ANSIColor

“This Ecma Standard defines control functions and their coded representations for use in a 7-bit code, an extended 7-bit code, an 8-bit code or an extended 8-bit code, if such a code is structured in accordance with Standard ECMA-35.”

Standard ECMA-48 - Control functions for coded character sets (5th edition) - June 1991 - Reprinted June 1998 – Ecma International - PDF

ECMA-48, 1st edition, March 1976 (not available), No file available

ECMA-48, 2nd edition, August 1979, Download

ECMA-48, 3rd edition, March 1984, Download

ECMA-48, 4th edition, December 1986, Download

“The place to look is in the extended capabilities, shown using the -x option of infocmp(1M), e.g.:

$ infocmp -1x | grep E3

would show

E3=\E[3J,

I used the -1 option to format the output as a single column.”

Further reading:

https://invisible-island.net/ncurses/

######## TERMINAL TYPE DESCRIPTIONS SOURCE FILE

#

# This version of terminfo.src is distributed with ncurses and is maintained

# by Thomas E. Dickey (TD).

---- snip ----

UNIX Lecture Notes - Chapter 4: Control of Disk and Terminal I/O - Prof. Stewart Weiss http://compsci.hunter.cuny.edu/~sweiss/course_materials/unix_lecture_notes/chapter_04.pdf

Concepts Covered:

File structure table, open file table, file status flags, auto-appending, device files, terminal devices, device drivers, line discipline, termios structure, terminal settings, canonical mode, non-canonical modes, IOCTLs, fcntl, ttyname, isatty, ctermid, getlogin, gethostname, tcgetattr, tcsetattr, tcflush, tcdrain, ioctl.

“The control terminal for a process is the terminal device from which keyboard-related signals may be generated. For example, if the user presses a Ctrl-C or Ctrl-D on terminal /dev/pts/2, all processes that have /dev/pts/2 as their control terminal will receive this signal.”

Using printf with escape sequences? - StackExchange

“Do you know that printf does not support hex backslash escapes? Your code is not portable as it relies on non-POSIX features.”

Where is the character escape sequence \033[\061m documented to mean bold?

MY NOTES:

Convert octal to decimal:

$ printf %d\\n 061

49

Convert octal to hexadecimal:

$ printf %x\\n 061

31

What protocol/standard is used by terminals?

ANSI Terminals

“xterm: A kind of amalgam of ANSI and the VT-whatever standards. Whenever you’re using a GUI terminal emulator like xterm or one of its derivatives, you’re usually also using the xterm terminal protocol, typically the more modern xterm-color or xterm-color256 variants.

. . .

A typical terminal emulator program is something of a mongrel, and doesn’t emulate any single terminal model exactly. It might support 96% of all DEC VT escape sequences up through the VT320, yet also support extensions like ANSI color (a VT525 feature) and an arbitrary number of rows and columns. The 4% of codes it doesn’t understand may not be missed if your programs don’t need those features, even though you’ve told curses (or whatever) that you want programs using it to use the VT320 protocol. Such a program might advertise itself as VT320 compatible, then, even though, strictly speaking, it is not.”

“AT&T promulgated terminfo as a replacement for BSD’s termcap database, and it was largely successful in replacing it, but there are still programs out there that still use the old termcap database. It is one of the many BSD vs. AT&T differences you can still find on modern systems.

My macOS box doesn’t have /etc/termcap, but it does have /usr/share/terminfo, whereas a standard installation of FreeBSD is the opposite way around, even though these two OSes are often quite similar at the command line level.

Properly-written Unix programs don’t emit these escape sequences directly. Instead, they use one of the libraries mentioned above, telling it to “move the cursor to position (1,1)” or whatever, and the library emits the necessary terminal control codes based on your TERM environment variable setting. This allows the program to work properly no matter what terminal type you run it on.

Old text terminals had a lot of strange features that didn’t get a lot of use by programs, so many popular terminal emulator programs simply don’t implement these features. Common omissions are support for sixel graphics and double-width/double-height text modes.

The maintainer of xterm wrote a program called vttest for testing VT terminal emulators such as xterm. You can run it against other terminal emulators to find out which features they do not support. “

$ printf '\033[1;34m%-6s\033[m' "This is blue text"

This is blue text$

$ printf '\033[1;33m%-6s\033[m' "This is yellow text"

This is yellow text$

$ printf '\033[1;31m%-6s\033[m' "This is red text"

This is red text$

Pseudo terminal (Pseudoterminal) - Wikipedia

“Variants

In the BSD PTY system, the slave device file, which generally has a name of the form /dev/tty[p-za-e][0-9a-f], supports all system calls applicable to text terminal devices. Thus it supports login sessions. The master device file, which generally has a name of the form /dev/pty[p-za-e][0-9a-f], is the endpoint for communication with the terminal emulator. With this [p-za-e] naming scheme, there can be at most 256 tty pairs. Also, finding the first free pty master can be racy unless a locking scheme is adopted. For that reason, recent BSD operating systems, such as FreeBSD, implement Unix98 PTYs.

BSD PTYs have been rendered obsolete by Unix98 - Single UNIX Specification ptys whose naming system does not limit the number of pseudo-terminals and access to which occurs without danger of race conditions. /dev/ptmx is the ‘pseudo-terminal master multiplexer’. Opening it returns a file descriptor of a master node and causes an associated slave node /dev/pts/N to be created.”

From man printf(1):

Character escape sequences are in backslash notation as defined in the

ANSI X3.159-1989 (“ANSI C89”), with extensions. The characters and their

meanings are as follows:

\a Write a <bell> character.

\b Write a <backspace> character.

\c Ignore remaining characters in this string.

\f Write a <form-feed> character.

\n Write a <new-line> character.

\r Write a <carriage return> character.

\t Write a <tab> character.

\v Write a <vertical tab> character.

\´ Write a <single quote> character.

\\ Write a backslash character.

\num Write a byte whose value is the 1-, 2-, or 3-digit octal

number num. Multibyte characters can be constructed using

multiple \num sequences.

Each format specification is introduced by the percent character (``%'').

The remainder of the format specification includes, in the following

order:

So:

$ printf %o\\n 65

101

$ printf '\101'

A$

$ printf '\101 \102 \103 \n'

A B C

$ printf '\033[9mTest\n\033[\060m' | od -c

0000000 033 [ 9 m T e s t \n 033 [ 0 m

0000015

$ printf '\033[9mCrossed-out characters.\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[1mBold. VT100\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[2mFaint\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[3mItalicized\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[4mUnderlined. VT100\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[5mBlink. VT100\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[7mInverse\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[8mInvisible (hidden)\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[9mCrossed-out characters.\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[21mDoubly-underlined.\n\033[\060m'

$ printf '\033[31mRed foreground.\n\033[\060m'

Red foreground.

$ printf '\033[32mGreen foreground.\n\033[\060m'

Green foreground.

$ printf '\033[33mYellow foreground.\n\033[\060m'

Yellow foreground.

$ printf '\033[34mBlue foreground.\n\033[\060m'

Blue foreground.

$ printf '\033[35mMagenta foreground.\n\033[\060m'

Magenta foreground.

ANSI Codes and Colorized Terminals

ANSI codes are embedded byte commands that are read by command-lines to output the text with special formatting or perform some task on the terminal output. The ANSI codes (or escape sequences) may appear as character codes rather than formatting codes. Terminals and terminal-emulators (such as Xterm) support many ANSI codes as well as some vendor-specific codes. Learning about ANSI may help terminal users to understand how it all works and allow developers to make better programs.

Control Characters (C0 and C1 Control Codes) are not the same as ANSI codes. Control characters are the commonly used CTRL+button combinations used in a terminal such as CTRL+C, CTRL+Z, CTRL+D, etc. In terminals, control characters may appear as “^C” (for “CTRL+C”) in the terminal output. For instance, in a terminal, press CTRL+C and then users will see “^C” in the terminal. The CTRL button provides a way to input the ESC character.

NOTE: The “ESC character” is not the same as the “ESC key”.

ANSI codes begin with the ESC character which appears as a carat (^) in terminals. The ESC character is then followed by ASCII characters which specifically tell the terminal what to do or how to display text. The ASCII character after the ESC character may be in the ASCII range “@” to “_” (64-95 ASCII decimal). However, more possibilities are available when using the two-character escape such as the carat and bracket (^[) which is known as the Control Sequence Introducer (CSI). CSI codes use “@” to “~” (64-126 ASCII decimal) after the escape. In ASCII hexadecimal, the ESC character is 0x1B or 33 in octal.

NOTE: The carat character is not the ESC character. Terminals use the carat symbol to display or represent the ESC character.

In a terminal, to type the CSI, type “\e[”. The “\e” acts as the ESC character and the “[” is the rest of the CSI. After typing the CSI, type the ASCII sequence needed to generate the desired output. For instance, in Xterm, typing “echo -e \e[S” will scroll the screen/output up one line. To scroll up more lines, place a number before the “S” which will act as a parameter - “echo -e \e[5S”.

MY NOTE: However in FreeBSD 12.x (tcsh shell, TERM = xterm-new, TERMCAP set?: Yes):

$ ps $$

PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND

95398 5 Ss 0:01.19 -tcsh (tcsh)

$ printf %s\\n "$SHELL"

/bin/tcsh

$ printf %s\\n "$TERM"

xterm-new

$ echo -e \\e[S

-e \e[S

$ set | grep echo

echo_style bsd

$ set echo_style = both

$ set | grep echo

echo_style both

$ echo -e \\e[S

-e

$ echo \\e[S

And, similarly:

$ echo \\e[H\e[2J

$ printf '\033[H\033[2J'

From STREAMS - Wikipedia:

In computer networking, STREAMS is the native framework in Unix System V for implementing character device drivers, network protocols, and inter-process communication. In this framework, a stream is a chain of coroutines that pass messages between a program and a device driver (or between a pair of programs). STREAMS originated in Version 8 Research Unix, as Streams (not capitalized).

STREAMS’s design is a modular architecture for implementing full-duplex I/O between kernel and device drivers. Its most frequent uses have been in developing terminal I/O (line discipline) and networking subsystems. In System V Release 4, the entire terminal interface was reimplemented using STREAMS. An important concept in STREAMS is the ability to push drivers - custom code modules which can modify the functionality of a network interface or other device - together to form a stack. Several of these drivers can be chained together in order.

…

The actual Streams modules live in kernel space on Unix, and are installed (pushed) and removed (popped) by the ioctl system call.

…

To perform input/output on a stream, one either uses the

readandwritesystem calls as with regular file descriptors, or a set of STREAMS-specific functions to send control messages.Ritchie admitted to regretting having to implement Streams in the kernel, rather than as processes, but felt compelled to do for reasons of efficiency. A later Plan 9 implementation did implement modules as user-level processes.

…

Implementations

…

FreeBSD has basic support for STREAMS-related system calls, as required by SVR4 binary compatibility layer.

From vt100.net - Terminals and Printers Handbook 1983-84 – Glossary – Appendix A – ASCII Codes:

“Both seven- and eight-bit ASCII codes are referenced here, as well as special graphics sets.”

7-Bit ASCII Code

---- snip ----

Control Characters

---- snip ----

Char Octal Binary

ESC 033 0011011

---- snip ----

Control Characters

+--------+-----------+-------+-------------------------------------+

| Name | Character | Octal | Function |

| | Mnemonic | Code | |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

+--------------------+-------+-------------------------------------+

| Escape | ESC | 033 | Processed as a sequence introducer. |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

+--------+-----------+-------+-------------------------------------+

Programmer Information

======================

Standard Character Set

----------------------

C0 Control Characters

---------------------

+--------+----------+-------+-------------------------------------+

| Name | Mnemonic | Octal | Function |

| | | Code | |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

+-------------------+-------+-------------------------------------+

| Escape | ESC | 033 | Introduces an escape sequence. |

| | | | When executed in graphics mode |

| | | | causes the terminal to exit and |

| | | | start processing the sequence. |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

+--------+----------+-------+-------------------------------------+

Graphics Mode C0 Control Characters

----------------------------------------

+------------+----------+-------+---------------------------------------------+

| Name | Mnemonic | Octal | Function |

| | | Code | |

+------------+----------+-------+---------------------------------------------+

| Cancel | CAN | 030 |Immediately causes an exit from graphics mode|

+------------+----------+-------+---------------------------------------------+

| Substitute | SUB | 032 |SUB is processed as a one column space |

+------------+----------+-------+---------------------------------------------+

| Escape | ESC | 033 |Causes the terminal to exit graphics mode and|

| | | |start processing the sequence |

+------------+----------+-------+---------------------------------------------+

---- snip ----

Escape and Control Sequences

-----------------------------

Note: V2 microcode supports the use of 8-bit characters to replace certain 7-bit sequences.

8-Bit Character [*] Equivalents for 7-Bit Escape Sequences

----------------------------------------------------------

+-----------------+---------------+-----------------------------+

| 7-Bit | 8-Bit | Function |

| Sequence | Character [*] | |

| | | |

| Octal | Octal | |

+-----------------+---------------+-----------------------------+

| | | |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

| | | |

| ESC [ 033 133 = CSI 233 | Control sequence introducer |

| | | |

| ---- snip ---- | | |

+-----------------+---------------+-----------------------------+

[*] V.2. only

From

Using csh & tcsh

By: Paul DuBois

Publisher: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Publication Date: July 1, 1995

Print ISBN-13: 978-1-56592-132-0

Preface

A shell is a command interpreter. You type commands into a shell, and the shell passes them to the computer for execution. UNIX systems usually provide several shell choices. This handbook focuses on two of the shells: C shell (csh) and an enhanced C shell (tcsh).

C shell (csh), a popular command interpreter that has its origins in Berkeley UNIX, is particularly suited for interactive use. It offers many features, including an ability to recall and modify previous commands, a facility for creating command shortcuts, shorthand notation for pathnames to home directories, and job control.

tcsh, an enhanced version of csh, is almost entirely upward compatible with csh, so whatever you know about the C shell you can apply immediately to tcsh. But tcsh goes beyond csh, adding capabilities like a general purpose command line editor, spelling correction, and programmable command, file, and user name completion.

Shells other than csh and tcsh may be available on your system. The two most significant examples are the Bourne shell (sh) and the Korn shell (ksh). The Bourne shell is the oldest of the currently popular shells and is the most widely available. The Korn shell was developed at AT&T and is most prevalent on System V-based UNIX systems. Both shells are fully documented elsewhere, so we won’t deal with them here.

…

Another reason for emphasizing interactive use over scripting is that csh and tcsh not good shells for writing scripts (Appendix C, Other Sources of Information, references a document that describes why). sh or perl are better for writing scripts, so there is little reason to discuss doing so with csh or tcsh.

Using csh & tcsh - Chapter 5. Setting Up Your Terminal

Identifying Your Terminal Settings

stty displays your current terminal settings. Its options vary from system to system, but at least one of the following command lines should produce output identifying several important terminal control functions and the characters you type to perform them:

% stty -a % stty all % stty everythingIn the output, look for something like this:

erase kill werase rprnt flush lnext susp intr quit stop eof ^? ^U ^W ^R ^O ^V ^Z ^C ^\ ^S/^Q ^DOr like this:

intr = ^c; quit = ^\; erase = ^?; kill = ^u; eof = ^d; start = ^q; stop = ^s; susp = ^z; rprnt = ^r; flush = ^o; werase = ^w; lnext = ^v;The words

erase,kill, etc., indicate terminal control functions. The^csequences indicate the characters that perform the functions. For example,^uand^UrepresentCTRL-U, and^?represents the DEL character.…

Footnote [6]: By terminal, I mean a keyboard-display combination. The display could be the screen of a real terminal, an xterm window running under X, or a screen managed by a terminal emulation program, running on a microcomputer.

From

Using csh & tcsh

By: Paul DuBois

Publisher: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Publication Date: July 1, 1995

Print ISBN-13: 978-1-56592-132-0

Using csh & tcsh - Chapter 5. What the Settings Mean

There are many special keys on your terminal; the most important are those that per form the

erase,kill,werase,rprnt,lnext,stop,start,intr,susp, andeoffunctions.Line Editing Settings

The

erase,kill,werase,rprnt, andlnextcharacters let you do simple editing of the current command line. (Some systems do not supportweraseorrprnt.) If you use tcsh, you also have access to a built-in general purpose editor, described in Chapter 7, The tcsh Command-Line Editor.…

lnextThelnext(literal-next) character lets you type characters into the command line that would otherwise be interpreted immediately. For instance, in tcsh,TABtriggers filename completion. To type a literalTABinto a command, type thelnextcharacter first. Thelnextcharacter is usuallyCTRL-V.

From

Using csh & tcsh

By: Paul DuBois

Publisher: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Publication Date: July 1, 1995

Print ISBN-13: 978-1-56592-132-0

Using csh & tcsh - Chapter 11. Quoting and Special Characters

This chapter describes how to quote special characters when you need to type them in a command line, as happens when a filename contains a space,

&, or*.Special Characters

The shell normally assigns special meanings to several characters (see Table 11-1). As you gain experience with the shell and learn these meanings, the fact that these characters are not interpreted literally tends to become a fact you take for granted. For example, after you know that

&signifies background execution and begin to use it accordingly, the convention becomes second-nature – part of your repertoire of shell-using skills.However, this set of skills is incomplete unless you also know how to use special characters literally, because sometimes you need to turn off their special meanings.

…

The Shell’s Quote Characters

Four characters are used for quoting. They turn off (or “escape”) special character meanings:

- A backslash (

\) turns off the special meaning of the following character.- Single quotes (

'…') turn off the special meaning of the characters between the quotes, except that!eventstill indicates history substitution.- Double quotes (

"…") turn off the special meaning of the characters between the quotes, except that!event,$var, and`cmd`still indicate history, variable, and command substitution. (You can think of double quotes as being “weaker” than single quotes because they turn off fewer special characters.)- The

lnext(“literal next”) character turns off the special meaning of the following character. (Thelnextcharacter is usuallyCTRL-V. See Chapter 5, Setting Up Your Terminal, for more information.) [NOTE] This character can be used with special characters that are otherwise interpreted as soon as they are typed. For example, in tcsh aTABtriggers filename completion; therefore, you cannot type a literal TAB unless you precede it withCTRL-V.…

Using csh & tcsh - Chapter 11. Quoting and Special Characters

Quoting Oddities

The quoting rules have a few exceptions. You probably won’t run into these often, but it’s good to be aware of them:

…

From

Unix in a Nutshell, 4th Edition

By: Arnold Robbins

Publisher: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Publication Date: October 26, 2005

Chapter 2. Unix Commands

…

2.2. Alphabetical Summary of Common Commands > stty

This list describes the commands that are common to two or more of Solaris, GNU/Linux, and Mac OS X. It also includes many programs available from the Internet that may not come “out of the box” on all the systems.

On Solaris, many of the Free Software and Open Source programs described here may be found in

/usr/sfw/binor/opt/sfw/bin. Interestingly, the Intel version of Solaris has more programs in/opt/sfw/binthan does the SPARC version. As mentioned earlier, on Solaris, we recommend placing/usr/xpg6/binand/usr/xpg4/binin your PATH before/usr/bin.…

Name

sttySynopsis

stty [options] [modes]Set terminal I/O options for the current device. Without options,

sttyreports the terminal settings, where a^indicates the Control key, and^'indicates a null value. Most modes can be switched using an optional preceding-(shown in brackets). The corresponding description is also shown in brackets.

From the man page for tcsh(1) on FreeBSD:

sequence-lead-in (arrow prefix, meta prefix, ^X)

Indicates that the following characters are part of a multi-key

sequence. Binding a command to a multi-key sequence really

creates two bindings: the first character to sequence-lead-in

and the whole sequence to the command. All sequences beginning

with a character bound to sequence-lead-in are effectively

bound to undefined-key unless bound to another command.

From the man page for tcsh(1) on FreeBSD:

Control characters in key can be literal (they can be typed by preceding them with the editor command quoted-insert, normally bound to

^V) or written caret-character style, e.g.,^A. Delete is written^?(caret-question mark).

key and command can contain backslashed escape sequences (in the style of System V echo(1)) as follows:

\a Bell

\b Backspace

\e Escape

\f Form feed

\n Newline

\r Carriage return

\t Horizontal tab

\v Vertical tab

\nnn The ASCII character corresponding to the octal

number nnn

`\' nullifies the special meaning of the following character,

if it has any, notably `\' and `^'.

---- snip ----

REFERENCE

The next sections of this manual describe all of the available Builtin

commands, Special aliases and Special shell variables.

Builtin commands

---- snip ----

bindkey [-l|-d|-e|-v|-u] (+)

bindkey [-a] [-b] [-k] [-r] [--] key (+)

bindkey [-a] [-b] [-k] [-c|-s] [--] key command (+)

Without options, the first form lists all bound keys and the

editor command to which each is bound, the second form lists

the editor command to which key is bound and the third form

binds the editor command command to key. Options include:

---- snip ----

-b key is interpreted as a control character written

^character (e.g., `^A') or C-character (e.g., `C-A'), a

meta character written M-character (e.g., `M-A'), a

function key written F-string (e.g., `F-string'), or an

extended prefix key written X-character (e.g., `X-A').

From the man page for tcsh(1) on FreeBSD:

Control characters can be written either in C-style-escaped notation, or in stty-like ^-notation.

The C-style notation adds

^[for Escape,_for a normal space character, and?for Delete. In addition, the^[escape character can be used to override the default interpretation of^[,^,:and=.

From POSIX terminal interface - Wikipedia

History > BSD: the advent of job control

See also:

[Job control (Unix) - POSIX terminal interface - Wikipedia((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/POSIX_terminal_interface#Job_control)

With the BSD Unices came job control, and a new terminal driver with extended capabilities. These extensions comprised additional (again programmatically modifiable) special characters:

- The “suspend” and “delayed suspend” characters (by default

Control+ZandControl+Y– ASCIISUBandEM) caused the generation of a new SIGTSTP signal to processes in the terminal’s controlling process group.- The “word erase”, “literal next”, and “reprint” characters (by default

Control+W,Control+V, andControl+R– ASCIIETB,SYN, andDC2) performed additional line editing functions. “word erase” erased the last word at the end of the line editing buffer. “literal next” allowed any special character to be entered into the line editing buffer (a function available, somewhat inconveniently, in Seventh Edition Unix via the backslash character). “reprint” caused the line discipline to reprint the current contents of the line editing buffer on a new line (useful for when another, background, process had generated output that had intermingled with line editing).The programmatic interface for querying and modifying all of these extra modes and control characters was still the ioctl() system call, which its creators (Leffler et al. 1989, p. 262) described as a “rather cluttered interface”. All of the original Seventh Edition Unix functionality was retained, and the new functionality was added via additional

ioctl()operation codes, resulting in a programmatic interface that had clearly grown, and that presented some duplication of functionality.

An annotated history of some character codes - or - ASCII: American Standard Code for Information Infiltration - by Tom Jennings

(Retrieved on Feb 18, 2024)

Most recently revised 12 April 2023 (typos and mention stunt box), previously revised 05 February 2020, previously revised 20 April 2016

Revision history:

https://www.sensitiveresearch.com/Archive/CharCodeHist/index.html#REVHIST

(Original: http://www.wps.com/projects/codes/X3.4-1963/index.html)

(Original: http://www.wps.com/projects/codes/X3.4-1963/page5.JPG)

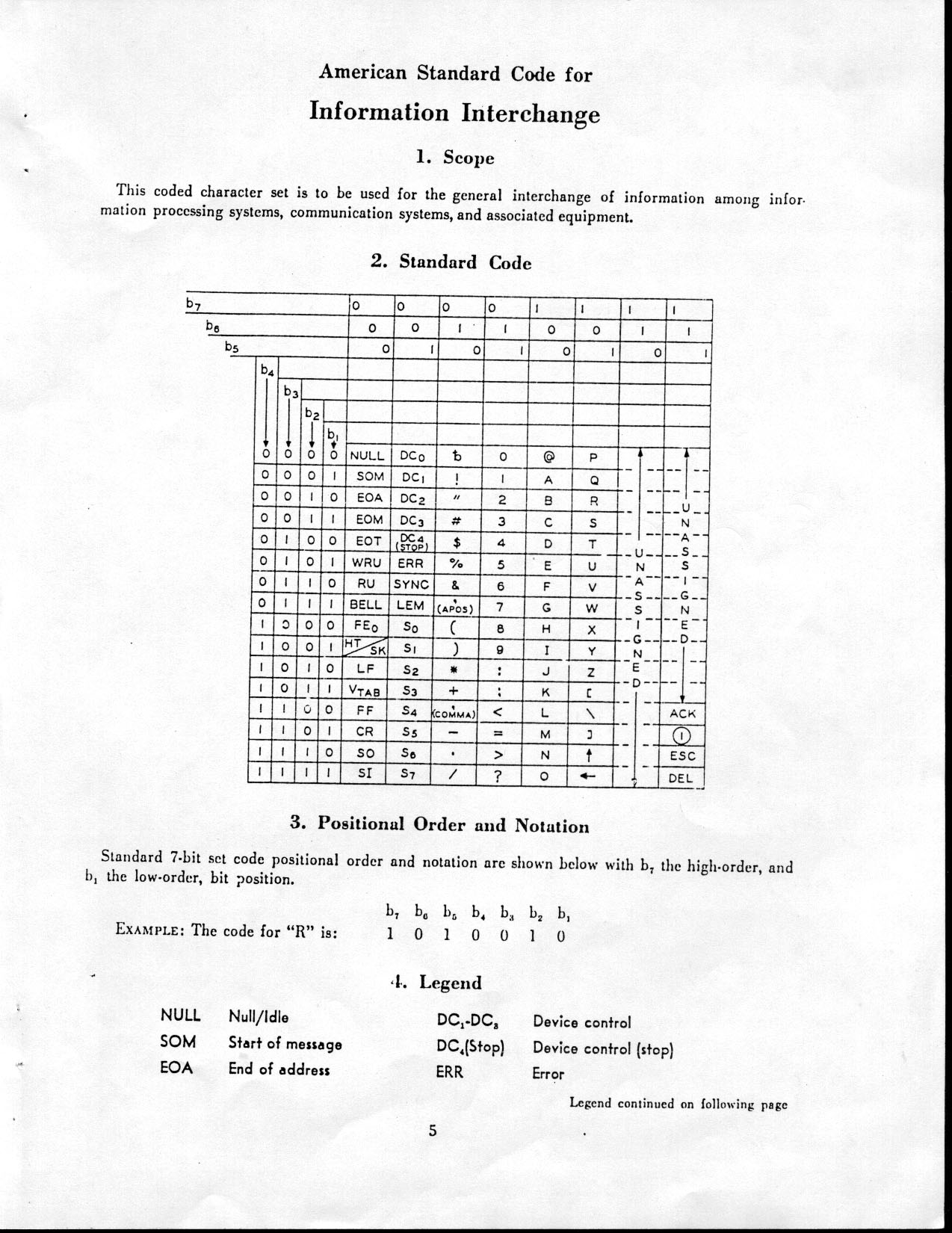

Overview

ASCII was developed in part from telegraph code. Its first commercial use was in the Teletype Model 33 and the Teletype Model 35 as a seven-bit teleprinter code promoted by Bell data services. Work on the ASCII standard began in May 1961, with the first meeting of the American Standards Association’s (ASA) (now the American National Standards Institute or ANSI) X3.2 subcommittee. The first edition of the standard was published in 1963, underwent a major revision during 1967, and experienced its most recent update during 1986. Compared to earlier telegraph codes, the proposed Bell code and ASCII were both ordered for more convenient sorting (i.e., alphabetization) of lists and added features for devices other than teleprinters.

The use of ASCII format for Network Interchange was described in 1969. That document was formally elevated to an Internet Standard in 2015.

Originally based on the (modern) English alphabet, ASCII encodes 128 specified characters into seven-bit integers as shown by the ASCII chart in this article:

RFC 4949 - Internet Security Glossary, Version 2 - Dr. Robert W. Shirey (August 2007)

Ninety-five of the encoded characters are printable: these include the digits 0 to 9, lowercase letters a to z, uppercase letters A to Z, and punctuation symbols. In addition, the original ASCII specification included 33 non-printing control codes which originated with Teletype models; most of these are now obsolete, (see note below ‘From Digital Electronics: Principles, Devices and Applications’) although a few are still commonly used, such as the carriage return, line feed, and tab codes.For example, lowercase

iwould be represented in the ASCII encoding by binary 1101001 = hexadecimal 69 (i is the ninth letter) = decimal 105.

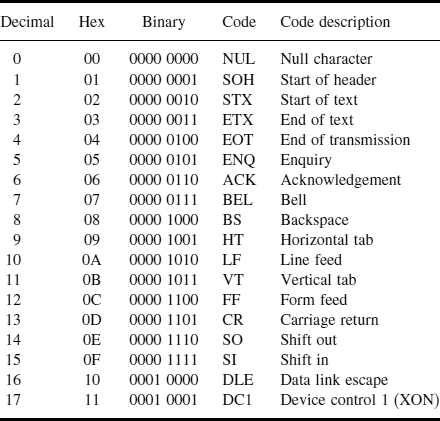

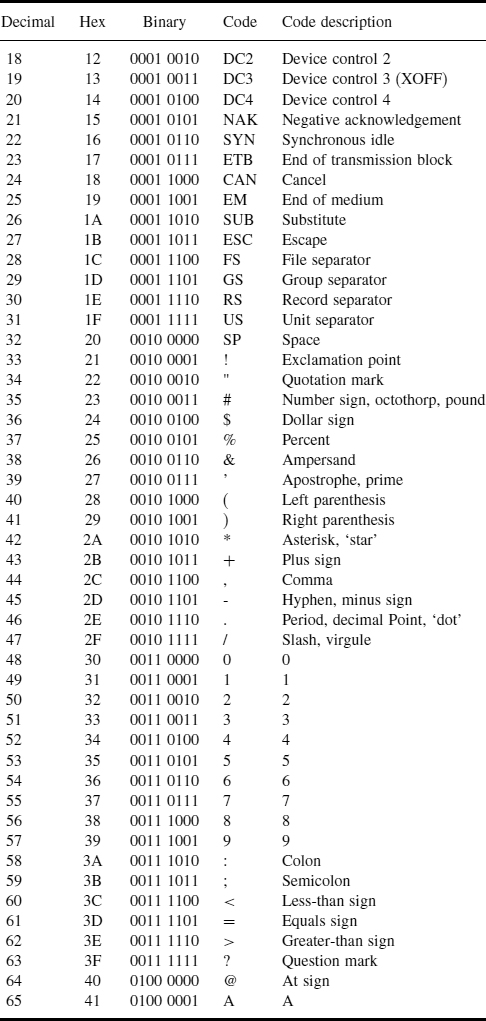

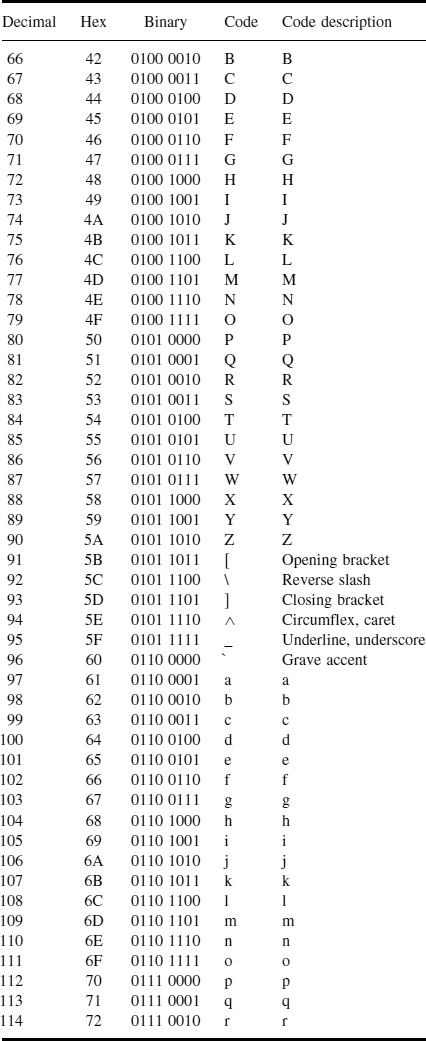

From Digital Electronics: Principles, Devices and Applications

By: Anil K. Maini

Published By: Wiley (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Publication Date: September 2007

Chapter 2. Binary Codes

2.4.1 ASCII code

The ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange), pronounced ‘ask-ee’, is strictly a seven-bit code based on the English alphabet. ASCII codes are used to represent alphanumeric data in computers, communications equipment and other related devices. The code was first published as a standard in 1967. It was subsequently updated and published as ANSI X3.4-1968, then as ANSI X3.4-1977 and finally as ANSI X3.4-1986. Since it is a seven-bit code, it can at the most represent 128 characters. It currently defines 95 printable characters including 26 upper-case letters (A to Z), 26 lower-case letters (a to z), 10 numerals (0 to 9) and 33 special characters including mathematical symbols, punctuation marks and space character. In addition, it defines codes for 33 nonprinting, mostly obsolete control characters that affect how text is processed. With the exception of ‘carriage return’ and/or ‘line feed’, all other characters have been rendered obsolete by modern mark-up languages and communication protocols, the shift from text-based devices to graphical devices and the elimination of teleprinters, punch cards and paper tapes. An eight-bit version of the ASCII code, known as US ASCII-8 or ASCII-8, has also been developed. The eight-bit version can represent a maximum of 256 characters.

Table 2.6 lists the ASCII codes for all 128 characters. When the ASCII code was introduced, many computers dealt with eight-bit groups (or bytes) as the smallest unit of information. The eighth bit was commonly used as a parity bit for error detection on communication lines and other device-specific functions. Machines that did not use the parity bit typically set the eighth bit to ‘0’.

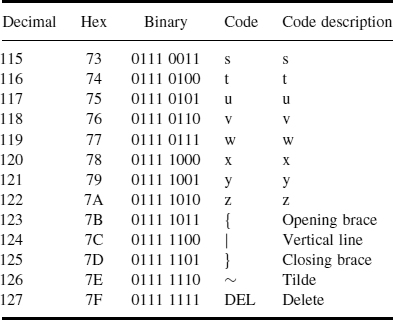

Table 2.6 ASCII code

Looking at the structural features of the code as reflected in Table 2.6, we can see that the digits 0 to 9 are represented with their binary values prefixed with 0011. That is, numerals 0 to 9 are represented by binary sequences from 0011 0000 to 0011 1001 respectively. Also, lower-case and upper-case letters differ in bit pattern by a single bit. While upper-case letters ‘A’ to ‘O’ are represented by 0100 0001 to 0100 1111, lower-case letters ‘a’ to ‘o’ are represented by 0110 0001 to 0110 1111. Similarly, while upper-case letters ‘P’ to ‘Z’ are represented by 0101 0000 to 0101 1010, lower-case letters ‘p’ to ‘z’ are represented by 0111 0000 to 0111 1010.

On FreeBSD, you can see the ASCII chart (ASCII table, aka ASCII character sets) by referring to the man page for ascii(7).

$ man ascii

ASCII(7) FreeBSD Miscellaneous Information Manual ASCII(7)

NAME

ascii – octal, hexadecimal, decimal and binary ASCII character sets

DESCRIPTION

The octal set:

000 NUL 001 SOH 002 STX 003 ETX 004 EOT 005 ENQ 006 ACK 007 BEL

010 BS 011 HT 012 LF 013 VT 014 FF 015 CR 016 SO 017 SI

020 DLE 021 DC1 022 DC2 023 DC3 024 DC4 025 NAK 026 SYN 027 ETB

030 CAN 031 EM 032 SUB 033 ESC 034 FS 035 GS 036 RS 037 US

040 SP 041 ! 042 " 043 # 044 $ 045 % 046 & 047 '

050 ( 051 ) 052 * 053 + 054 , 055 - 056 . 057 /

060 0 061 1 062 2 063 3 064 4 065 5 066 6 067 7

070 8 071 9 072 : 073 ; 074 < 075 = 076 > 077 ?

100 @ 101 A 102 B 103 C 104 D 105 E 106 F 107 G

110 H 111 I 112 J 113 K 114 L 115 M 116 N 117 O

120 P 121 Q 122 R 123 S 124 T 125 U 126 V 127 W

130 X 131 Y 132 Z 133 [ 134 \ 135 ] 136 ^ 137 _

140 ` 141 a 142 b 143 c 144 d 145 e 146 f 147 g

150 h 151 i 152 j 153 k 154 l 155 m 156 n 157 o

160 p 161 q 162 r 163 s 164 t 165 u 166 v 167 w

---- snip ----

From the man page for termios(4) on FreeBSD 13:

---- snip ----

The following special characters are extensions defined by this system

and are not a part of IEEE Std 1003.1 (“POSIX.1”) termios.

---- snip ----

LNEXT Special character on input and is recognized if the IEXTEN flag

is set. Receipt of this character causes the next character to

be taken literally.

---- snip ----

Local Modes

Values of the c_lflag field describe the control of various functions,

and are composed of the following masks.

ECHOKE /* visual erase for line kill */

ECHOE /* visually erase chars */

ECHO /* enable echoing */

ECHONL /* echo NL even if ECHO is off */

ECHOPRT /* visual erase mode for hardcopy */

ECHOCTL /* echo control chars as ^(Char) */

---- snip ----

If ECHOCTL is set, the system echoes control characters in a visible

fashion using a **caret** followed by the **control character**.

---- snip ----

Special Control Characters

The special control characters values are defined by the array c_cc.

This table lists the array index, the corresponding special character,

and the system default value. For an accurate list of the system

defaults, consult the header file <sys/ttydefaults.h>.

Index Name Special Character Default Value

VEOF EOF ^D

VEOL EOL _POSIX_VDISABLE

VEOL2 EOL2 _POSIX_VDISABLE

VERASE ERASE ^? ‘\177’

VWERASE WERASE ^W

VKILL KILL ^U

VREPRINT REPRINT ^R

VINTR INTR ^C

VQUIT QUIT ^\\ ‘\34’

VSUSP SUSP ^Z

VDSUSP DSUSP ^Y

VSTART START ^Q

VSTOP STOP ^S

VLNEXT LNEXT ^V

VDISCARD DISCARD ^O

VMIN --- 1

VTIME --- 0

VSTATUS STATUS ^T

---- snip ----

The initial values of the flags and control characters after open() is

set according to the values in the header <sys/ttydefaults.h>.

SEE ALSO

stty(1), tcgetsid(3), tcgetwinsize(3), tcsendbreak(3), tcsetattr(3),

tcsetsid(3), tty(4), stack(9)

$ wc -l /usr/include/sys/ttydefaults.h

112 /usr/include/sys/ttydefaults.h

$ cat /usr/include/sys/ttydefaults.h

/*-

* SPDX-License-Identifier: BSD-3-Clause

*

---- snip ----

*

* @(#)ttydefaults.h 8.4 (Berkeley) 1/21/94

*/

/*

* System wide defaults for terminal state.

*/

#ifndef _SYS_TTYDEFAULTS_H_

#define _SYS_TTYDEFAULTS_H_

/*

* Defaults on "first" open.

*/

#define TTYDEF_IFLAG (BRKINT | ICRNL | IMAXBEL | IXON | IXANY)

#define TTYDEF_OFLAG (OPOST | ONLCR)

#define TTYDEF_LFLAG_NOECHO (ICANON | ISIG | IEXTEN)

#define TTYDEF_LFLAG_ECHO (TTYDEF_LFLAG_NOECHO \

| ECHO | ECHOE | ECHOKE | ECHOCTL)

#define TTYDEF_LFLAG TTYDEF_LFLAG_ECHO

#define TTYDEF_CFLAG (CREAD | CS8 | HUPCL)

#define TTYDEF_SPEED (B9600)

/*

* Control Character Defaults

*/

/*

* XXX: A lot of code uses lowercase characters, but control-character

* conversion is actually only valid when applied to uppercase

* characters. We just treat lowercase characters as if they were

* inserted as uppercase.

*/

#define CTRL(x) ((x) >= 'a' && (x) <= 'z' ? \

((x) - 'a' + 1) : (((x) - 'A' + 1) & 0x7f))

#define CEOF CTRL('D')

#define CEOL 0xff /* XXX avoid _POSIX_VDISABLE */

#define CERASE CTRL('?')

#define CERASE2 CTRL('H')

#define CINTR CTRL('C')

#define CSTATUS CTRL('T')

#define CKILL CTRL('U')

#define CMIN 1

#define CQUIT CTRL('\\')

#define CSUSP CTRL('Z')

#define CTIME 0

#define CDSUSP CTRL('Y')

#define CSTART CTRL('Q')

#define CSTOP CTRL('S')

#define CLNEXT CTRL('V')

#define CDISCARD CTRL('O')

#define CWERASE CTRL('W')

#define CREPRINT CTRL('R')

#define CEOT CEOF

/* compat */

#define CBRK CEOL

#define CRPRNT CREPRINT

#define CFLUSH CDISCARD

/* PROTECTED INCLUSION ENDS HERE */

#endif /* !_SYS_TTYDEFAULTS_H_ */

/*

* #define TTYDEFCHARS to include an array of default control characters.

*/

#ifdef TTYDEFCHARS

#include <sys/cdefs.h>

#include <sys/_termios.h>

static const cc_t ttydefchars[] = {

CEOF, CEOL, CEOL, CERASE, CWERASE, CKILL, CREPRINT, CERASE2, CINTR,

CQUIT, CSUSP, CDSUSP, CSTART, CSTOP, CLNEXT, CDISCARD, CMIN, CTIME,

CSTATUS, _POSIX_VDISABLE

};

_Static_assert(sizeof(ttydefchars) / sizeof(cc_t) == NCCS,

"Size of ttydefchars does not match NCCS");

#undef TTYDEFCHARS

#endif /* TTYDEFCHARS */

$ grep CTRL /usr/include/sys/ttydefaults.h | grep V

#define CLNEXT CTRL('V')

From Things Every Hacker Once Knew - Eric S. Raymond (esr):

(Retrieved on Feb 18, 2024)

36-bit machines and the persistence of octal

There’s a power-of-two size hierarchy in memory units that we now think of as normal - 8 bit bytes, 16 or 32 or 64-bit words. But this did not become effectively universal until after 1983. There was an earlier tradition of designing computer architectures with 36-bit words. There was a time when 36-bit machines loomed large in hacker folklore and some of the basics about them were ubiquitous common knowledge, though cultural memory of this era began to fade in the early 1990s. Two of the best-known 36-bitters were the DEC PDP-10 and the Symbolics 3600 Lisp machine. The cancellation of the PDP-10 in ‘83 proved to be the death knell for this class of machine, though the 3600 fought a rear-guard action for a decade afterwards.

Hexadecimal is a natural way to represent raw memory contents on machines with the power-of-two size hierarchy. But octal (base-8) representations of machine words were common on 36-bit machines, related to the fact that a 36-bit word naturally divides into 12 3-bit fields naturally represented as octal. In fact, back then we generally assumed you could tell which of the 32- or 36-bit phyla a machine belonged in by whether you could see digits greater than 7 in a memory dump.

It used also to be generally known that 36-bit architectures explained some unfortunate features of the C language. The original Unix machine, the PDP-7, featured 18-bit words corresponding to half-words on larger 36-bit computers. These were more naturally represented as six octal (3-bit) digits.

The immediate ancestor of C was an interpreted language written on the PDP-7 and named B. In it, a numeric literal beginning with 0 was interpreted as octal.

The PDP-7’s successor, and the first workhorse Unix machine was the PDP-11 (first shipped in 1970). It had 16-bit words - but, due to some unusual peculiarities of the instruction set, octal made more sense for its machine code as well. C, first implemented on the PDP-11, thus inherited the B octal syntax. And extended it: when an in-string backslash has a following digit, that was expected to lead an octal literal.

The Interdata 32, VAX, and other later Unix platforms didn’t have those peculiarities; their opcodes expressed more naturally in hex. But C was never adjusted to prefer hex, and the surprising interpretation of leading 0 wasn’t removed.

Because many later languages (Java, Python, etc) copied C’s low-level lexical rules for compatibility reasons, the relatively useless and sometimes dangerous octal syntax besets computing platforms for which three-bit opcode fields are wildly inappropriate, and may never be entirely eradicated [3].

The PDP-11 was so successful that architectures strongly influenced by it (notably, including Intel [4] and ARM microprocessors) eventually took over the world, killing off 36-bit machines.

The x86 instruction set actually kept the property that though descriptions of its opcodes commonly use hex, large parts of the instructiion set are best understood as three-bit fields and thus best expressed in octal. This is perhaps clearest in the encoding of the mov instruction.

[3]. Python 3, Perl 6, and Rust have at least gotten rid of the dangerous leading-0-for-octal syntax, but Go kept it.

[4]. Early Intel microprocessors weren’t much like the PDP-11, but the 80286 and later converged with it in important ways.. . .

ASCII

ASCII, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, evolved in the early 1960s out of a family of character codes used on teletypes.

ASCII, unlike a lot of other early character encodings, is likely to live forever - because by design the low 127 code points of Unicode are ASCII. If you know what UTF-8 is (and you should) every ASCII file is correct UTF-8 as well.

The following table describes ASCII-1967, the version in use today. This is the 16x4 format given in most references.

Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex Dec Hex

0 00 NUL 16 10 DLE 32 20 48 30 0 64 40 @ 80 50 P 96 60 ` 112 70 p

1 01 SOH 17 11 DC1 33 21 ! 49 31 1 65 41 A 81 51 Q 97 61 a 113 71 q

2 02 STX 18 12 DC2 34 22 " 50 32 2 66 42 B 82 52 R 98 62 b 114 72 r

3 03 ETX 19 13 DC3 35 23 # 51 33 3 67 43 C 83 53 S 99 63 c 115 73 s

4 04 EOT 20 14 DC4 36 24 $ 52 34 4 68 44 D 84 54 T 100 64 d 116 74 t

5 05 ENQ 21 15 NAK 37 25 % 53 35 5 69 45 E 85 55 U 101 65 e 117 75 u

6 06 ACK 22 16 SYN 38 26 & 54 36 6 70 46 F 86 56 V 102 66 f 118 76 v

7 07 BEL 23 17 ETB 39 27 ' 55 37 7 71 47 G 87 57 W 103 67 g 119 77 w

8 08 BS 24 18 CAN 40 28 ( 56 38 8 72 48 H 88 58 X 104 68 h 120 78 x

9 09 HT 25 19 EM 41 29 ) 57 39 9 73 49 I 89 59 Y 105 69 i 121 79 y

10 0A LF 26 1A SUB 42 2A * 58 3A : 74 4A J 90 5A Z 106 6A j 122 7A z

11 0B VT 27 1B ESC 43 2B + 59 3B ; 75 4B K 91 5B [ 107 6B k 123 7B {

12 0C FF 28 1C FS 44 2C , 60 3C < 76 4C L 92 5C \ 108 6C l 124 7C |

13 0D CR 29 1D GS 45 2D - 61 3D = 77 4D M 93 5D ] 109 6D m 125 7D }

14 0E SO 30 1E RS 46 2E . 62 3E > 78 4E N 94 5E ^ 110 6E n 126 7E ~

15 0F SI 31 1F US 47 2F / 63 3F ? 79 4F O 95 5F _ 111 6F o 127 7F DEL

However, this format - less used because the shape is inconvenient - probably does more to explain the encoding:

0000000 NUL 0100000 1000000 @ 1100000 `

0000001 SOH 0100001 ! 1000001 A 1100001 a

0000010 STX 0100010 " 1000010 B 1100010 b

0000011 ETX 0100011 # 1000011 C 1100011 c

0000100 EOT 0100100 $ 1000100 D 1100100 d

0000101 ENQ 0100101 % 1000101 E 1100101 e

0000110 ACK 0100110 & 1000110 F 1100110 f

0000111 BEL 0100111 ' 1000111 G 1100111 g

0001000 BS 0101000 ( 1001000 H 1101000 h

0001001 HT 0101001 ) 1001001 I 1101001 i

0001010 LF 0101010 * 1001010 J 1101010 j

0001011 VT 0101011 + 1001011 K 1101011 k

0001100 FF 0101100 , 1001100 L 1101100 l

0001101 CR 0101101 - 1001101 M 1101101 m

0001110 SO 0101110 . 1001110 N 1101110 n

0001111 SI 0101111 / 1001111 O 1101111 o

0010000 DLE 0110000 0 1010000 P 1110000 p

0010001 DC1 0110001 1 1010001 Q 1110001 q

0010010 DC2 0110010 2 1010010 R 1110010 r

0010011 DC3 0110011 3 1010011 S 1110011 s

0010100 DC4 0110100 4 1010100 T 1110100 t

0010101 NAK 0110101 5 1010101 U 1110101 u

0010110 SYN 0110110 6 1010110 V 1110110 v

0010111 ETB 0110111 7 1010111 W 1110111 w

0011000 CAN 0111000 8 1011000 X 1111000 x

0011001 EM 0111001 9 1011001 Y 1111001 y

0011010 SUB 0111010 : 1011010 Z 1111010 z

0011011 ESC 0111011 ; 1011011 [ 1111011 {

0011100 FS 0111100 < 1011100 \ 1111100 |

0011101 GS 0111101 = 1011101 ] 1111101 }

0011110 RS 0111110 > 1011110 ^ 1111110 ~

0011111 US 0111111 ? 1011111 _ 1111111 DEL

Using the second table, it’s easier to understand a couple of things:

The Control modifier on your keyboard basically clears the top three bits of whatever character you type, leaving the bottom five and mapping it to the 0..31 range. So, for example, Ctrl-SPACE, Ctrl-@, and Ctrl-` all mean the same thing: NUL.

Very old keyboards used to do Shift just by toggling the 32 or 16 bit, depending on the key; this is why the relationship between small and capital letters in ASCII is so regular, and the relationship between numbers and symbols, and some pairs of symbols, is sort of regular if you squint at it. The ASR-33, which was an all-uppercase terminal, even let you generate some punctuation characters it didn’t have keys for by shifting the 16 bit; thus, for example, Shift-K (0x4B) became a [ (0x5B)

It used to be common knowledge that the original 1963 ASCII had been slightly different. It lacked tilde and vertical bar; 5E was an up-arrow rather than a caret, and 5F was a left arrow rather than underscore. Some early adopters (notably DEC) held to the 1963 version.

If you learned your chops after 1990 or so, the mysterious part of this is likely the control characters, code points 0-31. You probably know that C uses NUL as a string terminator. Others, notably LF = Line Feed and HT = Horizontal Tab, show up in plain text. But what about the rest?

Many of these are remnants from teletype protocols that have either been dead for a very long time or, if still live, are completely unknown in computing circles. A few had conventional meanings that were half-forgotten even before Internet times. A very few are still used in binary data protocols today.

Here’s a tour of the meanings these had in older computing, or retain today. If you feel an urge to send me more, remember that the emphasis here is on what was common knowledge back in the day. If I don’t know it now, we probably didn’t generally know it then.

. . .

SYN (Synchronous Idle) = Ctrl-V

Never to my knowledge used specially after teletypes, except in synchronous serial protocols never used on micros or minis. Be careful not to confuse this with the SYN (synchronization) packet used in TCP/IP’s SYN SYN-ACK initialization sequence. In an unrelated usage, many Unix tty drivers use this (as

Ctrl-V) for the literal-next character (aka lnext character) that lets you quote following control characters such asCtrl-C.…

Change history

1.0: 2017-01-26 Initial version.

…

1.22: 2023-04-19

From Things Every Hacker Once Knew (catb.org) - Hacker News dicussion:

(Retrieved on Feb 18, 2024)

soneil on Jan 27, 2017 [-]

I always thought it was a shame the ASCII table is rarely shown in columns (or rows) of 32, as it makes a lot of this quite obvious. e.g., http://pastebin.com/cdaga5i1

00 01 10 11 00000 NUL Spc @ ` 00001 SOH ! A a 00010 STX " B b 00011 ETX # C c 00100 EOT $ D d 00101 ENQ % E e 00110 ACK & F f 00111 BEL ' G g 01000 BS ( H h 01001 TAB ) I i 01010 LF * J j 01011 VT + K k 01100 FF , L l 01101 CR - M m 01110 SO . N n 01111 SI / O o 10000 DLE 0 P p 10001 DC1 1 Q q 10010 DC2 2 R r 10011 DC3 3 S s 10100 DC4 4 T t 10101 NAK 5 U u 10110 SYN 6 V v 10111 ETB 7 W w 11000 CAN 8 X x 11001 EM 9 Y y 11010 SUB : Z z 11011 ESC ; [ { 11100 FS < \ | 11101 GS = ] } 11110 RS > ^ ~ 11111 US ? _ DELIt becomes immediately obvious why, e.g.,

^[becomesescape. Or that the alphabet is just 40h + the ordinal position of the letter (or 60h for lower-case). Or that we shift between upper & lower-case with a single bit.esr’s (Eric S. Raymond) rendering of the table - forcing it to fit hexadecimal as eight groups of 4 bits, rather than four groups of 5 bits, makes the relationship between

^Iandtab, or^[andescape, nearly invisible.It’s like making the periodic table 16 elements wide because we’re partial to hex, and then wondering why no-one can spot the relationships anymore.

bogomipz - I am not following, can you explain why ^[ becomes escape

“It becomes immediately obvious why, eg, ^[ becomes escape. Or that the alphabet is just 40h + the ordinal position of the letter (or 60h for lower-case). Or that we shift between upper & lower-case with a single bit.”

Q: I am not following, can you explain why

^[becomesescape. Or that the alphabet is just 40h + the ordinal position? Can you elaborate? I feel like I am missing the elegance you are pointing out.A: If you look at each byte as being 2 bits of ‘group’ and 5 bits of ‘character’;

00 11011 is Escape 10 11011 is [So when we do

ctrl+[forescape(e.g., in old ANSI ‘escape sequences’, or in more recent discussions about the vim escape key on the ‘touchbar’ macbooks) - you’re asking for the character11011([) out of the control (00) set.Any time you see

\nrepresented as^M, it’s the same thing -01101(M) in the control (00) set isCarriage Return.Excerpt from the above table

00 01 10 11 ---- snip --- 01101 CR - M m ---- snip --- 11011 ESC ; [ {Likewise, when you realise that the relationship between upper-case and lower-case is just the same character from sets 10 & 11, it becomes obvious that you can, e.g., translate upper case to lower case by just doing a bitwise or against

64(0100000).

MY NOTE:

Convert binary 11011 to decimal:

+------------------------------+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | Number in binary | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | +------------------------------+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | Positional values | | | | | | | (2 to the power of) | 2^4 | 2^3 | 2^2 | 2^1 | 2^0 | +------------------------------+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | Product - From the row above | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | +------------------------------+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | ON or OFF | | | | | | | | | | | | | | (Look in the first column ) | ON | ON | OFF | ON | ON | | - From the first column: | | | | | | | 1 = ON | | | | | | | 0 = OFF | | | | | | +------------------------------+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

16 + 8 + 0 + 2 + 1=27So, binary

11011in decimal is27.

Convert decimal 27 to octal:

% printf "%03o\n" 27

033

Explanation:

“%03” - Column length for printf(1) is three digits, with zero-padding rather than blank-padding

ESC 033 00 11011

From Things Every Hacker Once Knew - Lobsters (lobste.rs) discussion:

(Retrieved on Feb 18, 2024)

A TTY-related fact that wasn’t mentioned in the article:

To control text-formatting on an ANSI-compatible terminal (or emulator), you can send it terminal control sequences like

\e[1mto enable bold or whatever. Paper-based terminals didn’t have control-sequences like that, but people still figured out ways to do formatting. For example, if you printed a letter, then sent backspace (Ctrl-H, octet0x08) and printed the same letter again, it would be printed with twice as much ink, making it look “bold”. If you printed a letter, then sent backspace and an underscore, it would look underlined.The original Unix typesetting software took full advantage of this trick. If you told it to output a document (say, a manpage) to your terminal (as opposed to the expensive typesetting machine in the corner), it would use the BS trick to approximate the intended formatting.

This worked great, up until the invention of video display terminals, where the backspace trick just replaced the original text, instead of adding to it. So people wrote software to translate the backspace-trick into ANSI control codes, software like

less(1).If you run:

printf 'H\x08He\x08el\x08ll\x08lo\x08o w\x08_o\x08_r\x08_l\x08_d\x08_\n'… in a modern terminal emulator, you’ll probably get output like (see MY NOTE below):

Hello _____… because that’s how glass TTYs work. However, if you pipe it through

less(1):printf 'H\x08He\x08el\x08ll\x08lo\x08o w\x08_o\x08_r\x08_l\x08_d\x08_\n' | less… it will convert the backspace trick into formatting your terminal can understand. Unfortunately, I can’t figure out how to represent it in Markdown, so you’ll have to try it for yourself.

MY NOTE:

In my test, it worked in bash but didn’t work in csh.

From Synchronous Idle - Wikipedia - archive.org snapshot from Dec 13, 2023:

Synchronous Idle (SYN) is the ASCII control character 22 (0x16), represented as

^Vin caret notation. In EBCDIC the corresponding character is 50 (0x32). Synchronous Idle is used in some synchronous serial communication systems such as Teletype machines or IBM’s Binary Synchronous (Bisync) protocol to provide a signal from which synchronous correction may be achieved between data terminal equipment.Because there is no START, STOP, or PARITY bits present in synchronous serial communication, it is necessary to establish character framing through recognition of consecutive SYN characters - typically three - at which point character sync can be assumed to begin with the first bit of the SYN characters and every seven bits thereafter.

The SYN character has the bit pattern 00010110 (EBCDIC 00110010), which has the property that it is distinct from any bit-wise rotation of itself. This helps bit-alignment of sequences of synchronous idles.

Unicode has a character U+2416 ␖ SYMBOL FOR SYNCHRONOUS IDLE for visual representation.

From ASCII character #22. Char SYN - Synchronous Idle:

About SYN:

Integer ASCII code: 22 Binary code: 0001 0110 Octal code: 26 Hexadecimal code: 16 Group: control Seq: ^VUnicode symbol: ␖, int code: 9238 (html ␖) hex code: 2416 (html ␖)

Information

It’s not hard to guess, that Synchronous Idle is used in synchronous transmission systems in order to make a signal. From this signal a synchronous correction may be accomplished between data terminal equipment, especially in cases when no other character is being transmitted.

Synchronous Idle (SYN) is the ASCII control character 22 (0x16). In caret notation SYN is designated as

^V. The appropriate character in EBCDIC is 50 (0x32). The Synchronous Idle is perfectly suitable for use in some synchronous serial communication systems, for example Teletype machines or the Binary Synchronous (Bisync) protocol. The use of Synchronous Idle here makes a signal. From it one can accomplish a synchronous correction between data terminal equipment, especially when no additional character is being transmitted.The SYN character possesses the following bit pattern: 00010110 (EBCDIC 00110010). It has one interesting feature: it is different from any bit-wise rotation of itself. This helps bit-alignment of synchronous idles sequences.

From the man page for lesskey(1) on FreeBSD 13:

LESSKEY(1) General Commands Manual LESSKEY(1)

NAME

lesskey - customize key bindings for less

SYNOPSIS (deprecated)

lesskey [-o output] [--] [input]

lesskey [--output=output] [--] [input]

lesskey -V

lesskey --version

---- snip ----

DESCRIPTION

A lesskey file specifies a set of key bindings and environment

variables to be used by subsequent invocations of less.

FILE FORMAT

The input file consists of one or more sections. Each section starts

with a line that identifies the type of section.

Possible sections are:

#command

Customizes command key bindings.

---- snip ----

COMMAND SECTION

The command section begins with the line

#command

If the command section is the first section in the file, this line may

be omitted. The command section consists of lines of the form:

string <whitespace> action [extra-string] <newline>

---- snip ----

The characters in the string may appear literally, or be prefixed by

a caret to indicate a control key. A backslash followed by one to

three octal digits may be used to specify a character by its octal

value. A backslash followed by certain characters specifies input

characters as follows:

\b BACKSPACE (0x08)

\e ESCAPE (0x1B)

\n NEWLINE (0x0A)

\r RETURN (0x0D)

\t TAB (0x09)

---- snip ----

From Unprintable ASCII characters and TTYs:

What happens when typing special “control sequences” like

<ctrl-h>,<ctrl-d>etc.?For convenience, “^X” means

Ctrl-Xin the following (ignoring the fact that you usually might use the lower case x).About a possible origin of the “^”-notation (aka caret notation), see also an article in a.f.c, 62097@bbn.BBN.COM

(local copy)

About a possible origin of the “^”-notation (aka caret notation), local copy: Re: Control characters - alt.folklore.computers - Jan 15, 1991

About a possible origin of the “^”-notation (aka caret notation), see also an article in a.f.c, 62097@bbn.BBN.COM – Control characters

Subject: Re: Control characters

From Why are special characters such as “carriage return” represented as “^M”?:

I believe that what OP was actually asking about is called Caret Notation.

Caret notation is a notation for unprintable control characters in ASCII encoding. The notation consists of a caret (^) followed by a capital letter; this digraph stands for the ASCII code that has the numerical value equivalent to the letter’s numerical value. For example the EOT character with a value of 4 is represented as ^D because D is the 4th letter in the alphabet. The NUL character with a value of 0 is represented as ^@ (@ is the ASCII character before A). The DEL character with the value 127 is usually represented as ^?, because the ASCII ‘?’ is before ‘@’ and -1 is the same as 127 if masked to 7 bits. An alternative formulation of the translation is that the printed character is found by inverting the 7th bit of the ASCII code

From the man page for less(1) on FreeBSD:

COMMANDS

In the following descriptions, ^X means control-X. ESC stands for the

ESCAPE key; for example ESC-v means the two character sequence

"ESCAPE", then "v".

---- snip ----

LINE EDITING

When entering command line at the bottom of the screen (for example, a

filename for the :e command, or the pattern for a search command),

certain keys can be used to manipulate the command line. Most commands

have an alternate form in [ brackets ] which can be used if a key does

not exist on a particular keyboard. (Note that the forms beginning

with ESC do not work in some MS-DOS and Windows systems because ESC is

the line erase character.) Any of these special keys may be entered

literally by preceding it with the "literal" character, either ^V or

^A. A backslash itself may also be entered literally by entering two

backslashes.

From the man page for curs_getch(3X) on FreeBSD:

Note that some keys may be the same as commonly used control keys,

e.g., KEY_ENTER versus control/M, KEY_BACKSPACE versus control/H. Some

curses implementations may differ according to whether they treat these

control keys specially (and ignore the terminfo), or use the terminfo

definitions. Ncurses uses the terminfo definition. If it says that

KEY_ENTER is control/M, getch will return KEY_ENTER when you press

control/M.

The stty utility sets certain terminal I/O options for the device that

is the current standard input. Without arguments, stty reports the set-

tings of certain options.

In this report, if a character is preceded by a caret (^), then the

value of that option is the corresponding control character (for exam-

ple, ^h is <CTRL-h>. In this case, recall that <CTRL-h> is the same as

the <BACKSPACE> key). The sequence ^@ means that an option has a null

value.

---- snip ----

Control Assignments

control-character c Set control-character to c, where:

control-character

is ctab, discard, dsusp, eof, eol, eol2,

erase, intr, kill, lnext, quit, reprint,

start, stop, susp, swtch, or werase (ctab

is used with -stappl, see termio(7I)).

For information on swtch, see NOTES.

c

If c is a single character, the control

character is set to that character.

In the POSIX locale, if c is preceded by a

caret (^) indicating an escape from the

shell and is one of those listed in the ^c